Show Cover Slide

gpt-4-turbohas translated this article into English.

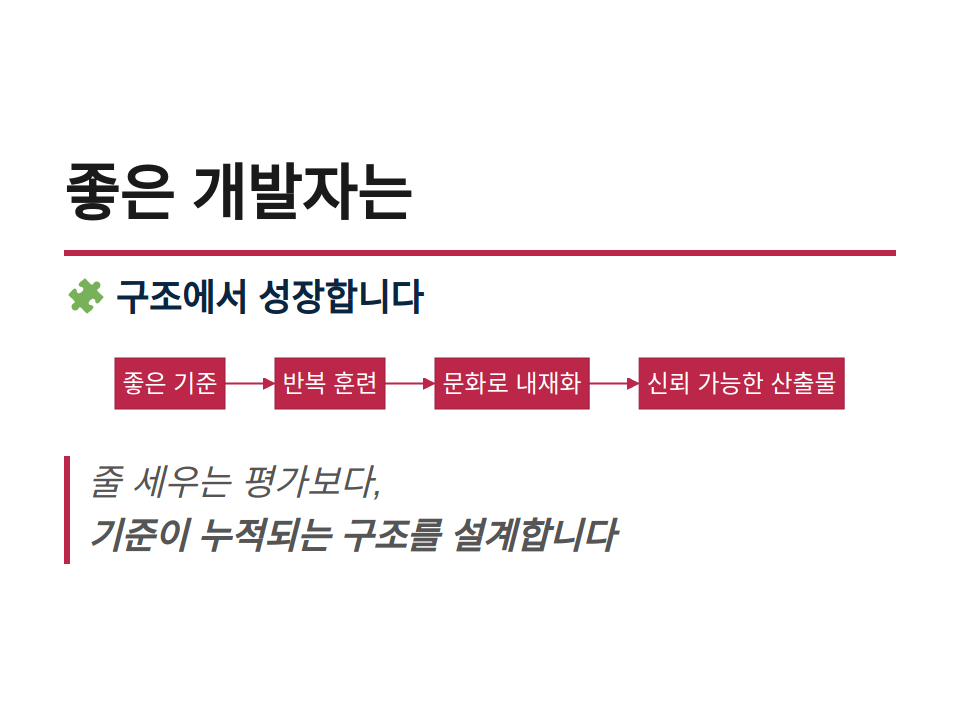

How Do Good Developers Grow Through Evaluation?

Performance evaluation is a sensitive and sometimes exhausting topic for developers.

However, if the desired image of a developer is clearly defined, evaluation can transform from a ranking tool into a method for growth and cultural training.

This is a discussion on how to define the criteria for a good developer, operate performance evaluation as a culture, and ultimately create a structure that accumulates reliable outputs in the team.

1. Why Should Evaluation Be for Culture?

Evaluating a developer’s performance is always challenging.

Just because someone created features quickly doesn’t mean they did well, and writing a lot of code doesn’t necessarily result in valuable outcomes.

Evaluation methods that only consider performance numerically can shrink the team, induce comparisons among developers, and strengthen competition rather than collaboration.

Instead of this approach, we first define “What do we mean by a good developer?” and based on these criteria, we aim to create a structure where the team can train repeatedly and grow.

The purpose of evaluation is not to rank but to establish standards that allow the team to grow together.

And these criteria will lead to outputs documented in code and papers, ultimately becoming the culture of the team itself.

2. Our Definition of a Good Developer

The criteria for judging a good developer are not fixed.

Technological stacks, projects, and teams vary.

Therefore, the first task is to define ‘What is a good developer?’ as a team.

Instead of seeking a universal criterion that applies to all situations, we gradually refine who our team wants to work with based on our own criteria.

This definition is not a checklist but a collection of philosophies and habits that the team develops as it grows.

Currently, the important criteria are as follows:

🧼 Expiry-Ready Code

Code should not be written to stay forever but structured to be deletable at any time.

We value code that won’t collapse the entire system if deleted more than just well-created functionalities.

Ideal code has low dependencies, segregated duties, and can adapt flexibly to changes in the domain.

To write Expiry-Ready code, consider the following:

- Where is this code intertwined?

- What modules would be affected if this feature was removed?

- Could this part be replaced or removed later?

Being Expiry-Ready is a key indicator of maintainability and scalability, and we train this structural flexibility as part of our team culture.

🧪 Mock-Up Focused Thinking

Design starts with imagining how something will be used before it is fully implemented.

Before coding, we value the habit of first drafting mock-up code.

Imagining how functions will be called, what results are expected, and in what context features will be used can lead us to design responsibilities and boundaries much more clearly.

This approach provides the following benefits:

- Allows defining the desired usage by callers first

- Filters overly complex structures beforehand

- Enhances clarity and consistency of interfaces

Don’t write code first; draw how it will be used first. We call this ‘Mock-Up Focused Thinking’.

🔗 Clear Call Interfaces

When calling a function or method, there shouldn’t be a question like, “What does this code do?”

A good interface simplifies context rather than hiding code complexity and is key to smooth collaboration.

We consider the following important:

- Predictable inputs and outputs

- Functions with a single responsibility

- Names that make context understandable at a glance

A clear call interface is the starting point for collaboration.

🧠 Domain-Informed Naming

Names are the first manual read in the code.

We believe that names of variables, instances, functions, and classes should explain their roles.

We adhere to two principles:

-

Name with at least two words

- Use domain-revealing names like

userProfile,paymentResultinstead of generic names likedata,obj.

- Use domain-revealing names like

-

IDEs are our tools.

- Long names are not an issue in an environment with autocompletion.

- They rather facilitate searching, tracking, and collaboration.

Good naming reveals understanding of the domain and is the first step in organizing team language.

📝 Documentation Considers the Reader

Documentation is not just explanation; it’s consideration.

We value naturally conveying the reasons behind decisions, choices made, and problems solved through structure and naming over just comments.

We prioritize the following over comments:

- Explaining context through code structure and naming

- Making the flow understandable through function names, file organization, and responsibility segregation

- Documenting complex decisions in wikis, PR descriptions, READMEs, etc.

If the code itself reads well, it is the best documentation.

📆 Readability with Maintenance in Mind

Good code is evaluated not now, but when it is maintained later.

It’s crucial whether the code can be modified by someone else in six months or a year rather than today.

We see readability not just as style but as a standard of sustainability and collaboration.

Features of good code:

- Separated roles and minimal overlap

- Naming that explains the domain context

- Remaining reasons for intentions and decisions

“Can another developer understand and modify this code at first glance?”

If the answer is yes, it’s a success.

🍝 Complex Code Requires Effort to Explain

Complex code itself is not a problem.

The problem is leaving it unexplained.

Anyone can write spaghetti-like code while quickly responding or dealing with complex domains.

We don’t forbid such code.

However, if that code remains within the team, the effort to explain the reasoning and decisions at that moment is absolutely necessary.

The important thing is not perfect documentation.

What the developer left at that time

- A few lines of comments

- A PR description

- Wiki links

- A line in a README

- Meaningfully named variables or functions

Any ‘attempt to explain’ itself represents that person’s willingness to grow and a considerate attitude toward the team.

We train to leave explanations anywhere, like PR descriptions, wikis, READMEs, comments, and make it a team culture.

Spaghetti code with explanations is a technical judgment,

while spaghetti code without explanations is a technical debt.

3. What We Leave Behind Matters More Than Quantity

When performance starts to be judged by numbers, developers focus on quickly creating many features or writing more lines of code.

However, we know.

Doing a lot doesn’t mean doing well. What really matters is “What did you leave behind?”

The simplest question to judge whether this code is good is this:

“Can a new person come in, understand this code, and participate?”

If the answer to this question is “yes,” then this code is not just a functional code but a structure where knowledge survives, and it is an output containing context and intent, not just quantity.

We do not base on:

- Number of commits

- Number of code lines

- Number of features

- Number of repeated modifications

Instead, we base on:

- Code that can explain the intent

- Documentation that reveals the context

- Structures that consider the reader

When these standards are repeated, the evaluation becomes the language of the team.

And we say this:

If there is unexplained spaghetti code left, that person probably hasn’t yet understood what our team means by ‘a good developer’.

Because the team has a culture that speaks through outputs, not results.

We think this:

Regardless of the project, information must remain documented so that onboarding is possible anytime for anyone.

The mentioned documents don’t necessarily have to be text.

README.mddocker-compose.yml,setenv.sh,Makefile,run.sh- Initial DB schema, sample data

- Mock APIs for frontend development

- Shell commands for testing, seed files

All these executable tools are onboarding documents, a sign of the team’s consideration, and a trace of culture.

And if nothing remains,

That person did not understand the culture of the team.

We are not a team that just shares knowledge.

We are a team that makes knowledge survive.

4. Evaluation Structure: A Trainable 3-Step Process

We designed the evaluation not as a judgment on results but as a training process to internalize team culture and foster growth.

Evaluation Phases Summary

| Phase | Actor | Purpose | Key Question |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | Self-Evaluation | Reflect on alignment with standards | “Am I working in this way?” |

| Phase 2 | Peer Evaluation | Empathy and feedback on team standards | “Are my colleagues working in this way?” |

| Phase 3 | Leader Judgment | Assess domain relevance and practical contribution | “Did this code align with actual business needs?” |

🪞 Self-Evaluation – The Start of Internalization

- Developers reflect on whether their work aligns with team standards

- Not just listing results, but a self-check focused on intent and context

🤝 Peer Evaluation – A Time for Empathy and Confirmation

- A process where colleagues exchange feedback based on standards

- Sharing how much each execution resonates with the standards

Peer evaluation should not be formally included in evaluations.

This process is a tool to check the degree of cultural internalization.

- It is not a means for comparison or ranking

- Rather, it can be a factor that destroys trust if the culture is not well-established

Peer evaluation is a tool for training and empathy, not an official criterion.

To reduce misunderstandings, it might be conducted after the evaluation announcement

This process is used only to check the degree of cultural understanding and standard internalization.

It is not a tool for comparison or ranking.

If not clearly understood, peer evaluation can harm rather than build trust.

Thus, we educate all team members that “peer evaluation is a tool for empathy and training” and we train repeatedly.

🎯 Leader Judgment – The Interpreter of Business Relevance

- Domain relevance and practical contribution are judged most qualitatively

- The team leader or manager assesses how well the output aligned with business objectives

Through these three phases,

we believe that qualitative standards can be trained repeatedly without quantitative comparisons.

Performance should be revealed not by results,

but by understanding and executing standards within the process.

5. Tools and Structures Used

No matter how good the evaluation criteria are,

without a structure to record, repeat, and reflect on these standards, it’s difficult to establish them as culture.

We operate the team so that standards are naturally recorded, shared, and accumulated through the following tools and habits.

🛠️ We Do Not Conduct PR Reviews

We do not follow the traditional PR cycle of creating features and then receiving approval.

We operate a standard checking process for refactoring.

This process is not a procedure to check code consistency.

It’s a structured dialogue time to read together the standards of a good developer defined by the team and train those standards in the code.

These standards are checked through the following questions:

- Was this code designed considering being Expiry-Ready?

- Does it read naturally without documentation?

- Was it designed by first imagining the usage through Mock-Up Focused Thinking?

- For complex structures or implementations, was no explanation omitted?

- Does it understand the domain, and are the terms and naming aligned?

We call this structure “Refactoring Day” and execute it like a PR at the end of the sprint schedule.

We do not conduct PR reviews.

We operate a process for refactoring.

However, we use Git’s PR feature as a means.

After a Refactoring Day,

- Traces of checking the standards remain,

- And commits, PRs, exchanged comments, documented intentions

ultimately accumulate as important outputs.

These records are not just work histories but intellectual assets containing the team’s thought process, domain judgments, and technical context.

In this structure, there is no longer an ‘approver’.

It’s not important who approves and who gives feedback; the process itself of everyone checking the code against the standards and recalling those standards becomes the team culture.

As self-review becomes possible, the standards become not just external feedback, but internalized habits.

This repetition ultimately helps the entire team to become a trained group that can create good code without needing approval.

📘 Knowledge Base (Wiki, Notion, etc.)

- We document domain understanding and decision-making flows derived from PRs, meetings, and retrospectives.

- It serves as the central hub for organizing and sharing team standards.

- The more records remain, the clearer the team’s standards become.

🪞 Self-Evaluation & Retrospective Template

- Helps individuals to reflect on and train according to the standards

- Ensures that standards are internalized through repeated execution

- Used not for evaluation purposes but as a reminder and training tool

🧠 Leader’s Judgment Sheet (Qualitative Evaluation)

- Focuses on domain relevance, actual usage, and completion of outputs rather than numbers

- Evaluates business contributions and visible execution traces in outputs

- Aims for a system where code and records speak, not people

We do not view these tools as evaluation tools.

We see them as structures that allow the team to repeat and train the way they work.

6. Conclusion: Designing Accumulation Rather than Evaluation

We do not want to rank people through evaluations.

We aim to agree on common standards for what makes a good developer and based on these standards, create a structure that allows the team to grow independently.

Performance should be verified not by numerical results but by outputs containing judgment intents and domain understanding.

And these outputs should remain as traces accumulated in the team through PRs, documentation, reviews, and retrospectives.

This is how we work

- Define standards first

- Create a trainable structure

- Design a trustworthy review culture

- Internalize standards through repeated execution

A good team does not need evaluations.

Within a structure where standards accumulate into culture, the team naturally produces good developers.

This is why we designed evaluations, how we operate the team, and how the culture functions.

Go Home